JOHN WISNIEWSKI: What first interested you in the writing of Charles Bukowski?

Daniel Weizmann: Bukowski was just always there, like the sun and the moon, I can’t really remember a day of discovery. I grew up in East Hollywood, a few blocks from Chatterton’s Bookstore, which was kind of a literary hub in the 1970s, the years of my childhood. And his books were always on display, each one as they came out. I was a grade school latchkey kid with nothing to do, so I’d kill hours and hours at Chatterton’s and occasionally stuff a few titles into my backpack unnoticed. I’m glad I never got caught!

But if it seems odd that a ten-year-old would even care, it’s because I had been primed for radical poetry. My mom and her friend Lenora were two of the original beats, really proto-beats, they were friends with Ginsberg and Carl Solomon at Brooklyn College, total post-war Village runaways. So I’d received a double-dose of free verse at a young age. After Archy and Mehitabel and The Wasteland, reading Bukowski was a relief, because he was representing our turf. This was the guy from the LA Free Press, the newspaper my hippie older brother Moshe brought home.

You see, Bukowski was really a local hero first, and I think that’s an important facet to his powers. Part of what made him so electric was the intense gaze he placed on a zone nobody else seemed to care about. It wasn’t the Hollywood of movies or myth, it wasn’t even the Los Angeles of Chandler’s grand sweeping vision. Bukowski wrote about the actual awkward shlumpy cowtown of our day to day lives. LA was not awake to itself back then, somehow, not really. And one of the first things I remember reading by Buk mentioned staggering hungover past a bowling alley off Hollywood Boulevard, which was the place my Aunt Ethel took me every week in summers. And I thought — this guy is writing about that ?! That crappy too-dark bowling alley with the little 25-cent vending machines that dispense needle and thread in plastic eggs? He gave it spiritual majesty.

JOHN: Did you ever get a chance to meet Bukowski?

DANIEL: I never did. When he first died I sorely regretted it, but now I’m not so sure it’s such a bad thing. Meeting heroes is risky enough and as you know, Bukowski could be rough on fans. See the “Bukowski Spit in My Face” piece for Exhibit A. About a year after he passed away, I did a reading at the Met Theater and got a lot of laughs. And his widow came up to me and said, “Oh Hank would’ve loved you.” Who am I to say she’s wrong? 🙂

JOHN: What was it like editing the rememberances of Bukowski by those who knew him, for your book?

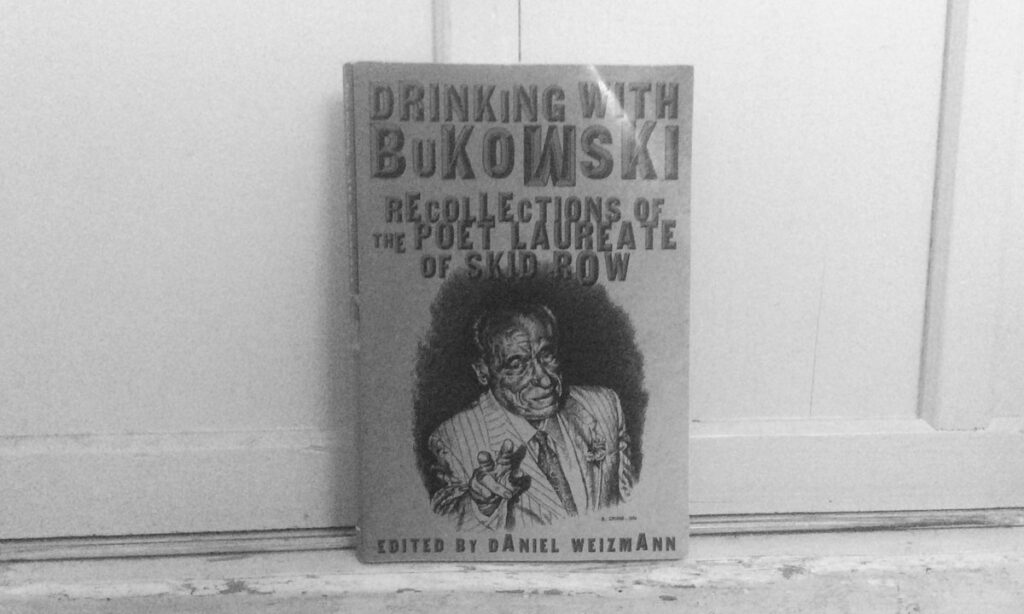

DANIEL: Very strange, and weirdly difficult. I was living in Manhattan and I’d just quit my job in special events for Central Park.I was totally lost. I didn’t want to go back to book publishing but someone introduced me to Neil Ortenberg, who had Thunder’s Mouth Press, and he had a great sensibility, a great vibe. First he made me the as-told-to for DeeDee Ramone’s Lobotomy autobio, then I edited Timothy Leary’s last batch of writings for him. Then he got this idea: Let’s do a tribute to Bukowski.

I was naive–it sounded like it would be a breeze, but I quickly learned how hard an anthology is to produce. Doing a tribute book like that is political in a way that I’m not. You have to make sure all the key people are represented, and you have to make everyone feel they’re front and center. Everyone has something to say about Charles Bukowski, that’s part of what makes him the giant and the conundrum that he is. There’s a great mistrust, too, when you’re talking about a literary figure who has recently died — like, are we here to exalt him, mummify him, air dirty laundry, are we vultures, are we adoring fans blinded by loss, or what? People had to be coaxed.

My friend Harvey Kubernik who had been the production coordinator for Bukowski’s Hostage LP was instrumental in helping me pull it off and deal with the many personalities — everyone from Sean Penn to Wanda Coleman, Neeli Cherkovki to R. Crumb to Hank’s ex-girlfriends and ex-wives. There were some heated calls and some angry answering machine messages, but once people understood that we wanted to show Hank’s life from the people who actually knew him, they got it. I remember going into the New York Public Library, the great reading room, with this heavy backpack, all manuscript pages, and sitting there all day, poring over the pages. It was surreal to be communing with Bukowski’s world so far from Chatterton’s Bookstore!

JOHN: Could you tell us about the book “The delicious Grace of moving one’s own hand” about Timothy Leary? How did you get interested in Timothy Leary’s Work?

DANIEL: The truth is, when I was dropping acid in the days of the Paisley Underground, I didn’t take Leary very seriously. The romance of Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters and the psychedelic rock scene were much more thrilling to me. I’d met him at his last birthday party, which was kind of a goofy Beverly Hills bash with nitrous oxide tanks and supermodels and everything. So when they gave me the assignment I was a little reluctant. They handed me a giant box, everything he wrote that was unpublished at the time he died. And I thought, “Oh man, this is gonna be a pain in the ass.” I was expecting a lot of cosmic gibberish.

What I didn’t understand is that Professor Leary was a serious psychologist, a humanist of the old school, and somebody who cared very deeply about the way that mind-state shapes our experience of life, how we carry the past, how we carry trauma, the way emotions distort or enhance our vision. I mean, his ideas just floored me — he was a frank and, in some ways, very anti-utopian thinker.

Leary’s been cartoonized by the media, but I hope his writings and his ideas will outlast his drug busts. We take all these advances in psychology for granted now, but they’re a part of everyday life — Gestalt, mindfulness, games people play, Maslow’s pyramid…Leary is in the front guard of that revolution. Like a lot of that generation that lived through World War II, he wanted to help humanity out of its rut. To that generation, consciousness expansion wasn’t recreation, it was a matter of life and death for the species. And, well, maybe they were right.

JOHN: Could you tell us about your early days, Daniel? How did you begin writing and editing?

DANIEL: My big claim to fame is, when I was 8 or 9, my older sister was dating the playwright Miguel Pinero, and he read some of my poetry. And he said, “Holy shit, this kid is for real.” That was all the incentive I needed. Then I started a punk fanzine called Rag in Chains when I was 13, and made xeroxes with my bar mitzvah money. And from there I went on to write for Flipside, then the LA Weekly where I did a column about being a high school student. The column thing — what a great form! You could pour your whole life into it, random thoughts and incidents, sudden left turns, rants and freakouts. I think Bukowski’s columns might be his best writing. Maybe. Definitely his most disarming.

Anyway my column led to participating in this very unusual and exciting spoken word revolution of the early Eighties that was being spearheaded by Kubernik — you had serious poets like Wanda Coleman and Holly Prado alongside rock and roll people like John Doe and Exene, Henry Rollins, Jello Biafra, and also old Hollywood characters like Vampira, . It was anything goes, just don’t be boring, which is probably the single greatest lesson a writer can get.

I started editing in my twenties, when Larry Sloan and Leonard Stern hired me to work on Mad Libs. I’d already been writing some gag lines for comics, writing rhymes for rappers. I would take any gig that came my way. When Price Stern Sloan sold the company, I went to New York to oversee the transition.

JOHN: Could you tell us about any upcoming projects?

DANIEL: For several years now, I’ve been working on an amateur detective mystery series. The first book is just about finished and I’m into the sequel. It’s my passion, the secret dream I’ve carried since childhood…It only took me four decades to work up the courage to get started!

It might seem like a leap, you know…from writing about poets like Bukowski to getting involved in crime fiction, but one funny thing I’ve noticed is that many of my cultural heroes absorbed the mood of detective noir, even if they didn’t deploy the strategies of mystery fiction itself. Bukowski, for instance, definitely owes a debt to Chandler and Bogart. He himself could have been a character on Dragnet. In a way, you could see Buk like a detective without a case.

Or take a movie like “Choose Me” or a song like “Glamour Profession” by Steely Dan—there’s a noir sensibility, an understanding of metropolitan aloneness and confusion, even when there isn’t a specific crime to be solved.

JOHN: Could you tell us about writing your memoir “We’ll Sing in the Sunshine”?

DANIEL: Well I started trying to writing a memoir about my father and older brother after they both died six months apart. I was staggering around in a state of shock, writing to “keep them in the room” or not let them go. Two larger-than-life figures to me and, of course, I found capturing their essence totally impossible. My dad grew up in Casablanca, he fought on the front lines in four wars and was the first Moroccan member of Palmach, the Israeli independence army. A real warrior. My brother was a radical hippie on the streets of Los Angeles in the late ‘60s.

Like I said, I never did manage to pull off the memoir. Slowly but surely, though, the unused material I had took a left turn and morphed into my second detective novel.

JOHN: You’ve written about Jim Morrison. What interested you about him?

DANIEL: I wrote an essay on Morrison recently for Harvey Kubernik’s cool compendium, SUMMER’S GONE. Morrison’s a perfect example of what I was talking about before – someone who grasped the root ambience of hardboiled crime fiction but shot it through a different medium. He put Chandler to the popular song. Actually my essay in that book is called, “Motel Money Murder Madness: Jim Morrison and the L.A. Noir Tradition.”

People make fun of Morrison. Readers of serious literature think he was a…you know, just a maudlin pretty boy. But Morrison is one of those people like Elizabeth Taylor where, if you can get past the fame and the hoopla, the cult of personality, there’s real artistry. Did you stop to consider how it will feel, cold, grinding grizzly bear jaws hot on your heels?

Bukowski, Morrison…all this stuff is like the custom cars in Tom Wolfe’s Tangerine-Flaked Streamline Baby, it’s all native Southern California art, made off the grid. In a land where nobody cares about poetry too much. The older I get, the more miraculous that seems.