Interview by John Wisniewski

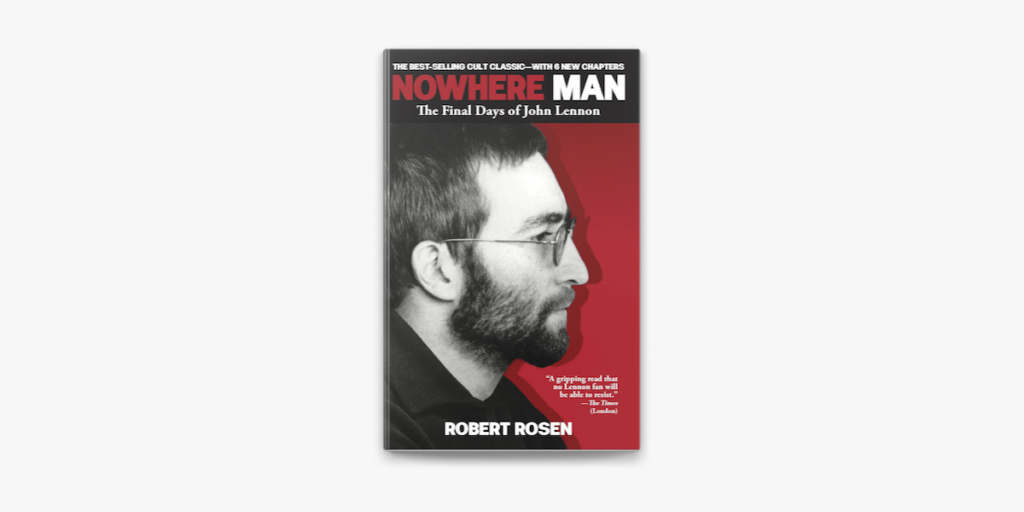

The book disputes the official view of Lennon as a contented househusband raising his son Sean and baking bread while Yoko ran the family business. Instead, Nowhere Man portrays Lennon’s daily life at the Dakota as that of a “tormented superstar, a prisoner of his fame, locked in his bedroom raving about Jesus Christ, while a retinue of servants tended to his every need.”

John Lennon’s diaries were given to Rosen in 1981 by Frederic Seaman, Lennon’s personal assistant.Seaman and Rosen were old friends from working at the OP in college. According to Rosen, Seaman told Rosen that Lennon had given him permission to use the diaries as source material for a biography that Seaman was to write in the event of Lennon’s death. Five days after Lennon’s murder, Seaman asked Rosen to help him with the project.

According to Rosen’s testimony at Seaman’s copyright infringement trial in September 2002, Seaman sent Rosen out of town in February 1982 and then ransacked his apartment, taking everything Rosen had been working on, including Lennon’s diaries, photocopies of the diaries, transcripts of the diaries, and a rough draft of the manuscript.

AMFM Magazine: Why did John Lennon choose to isolate himself during the 70s?

It was a combination of factors. Primarily, when Sean was born in 1975, John looked upon the new baby as a last-chance opportunity to repent for all his past sins against family. He’d never reconciled his guilt over the way he’d deserted his first wife, Cynthia, and their son, Julian, for Yoko. So John decided that he’d devote the next five years to being a real father to Sean. Which he did—with a lot of help from assorted nannies and servants.

The other reason was that the music business had left him creatively drained and emotionally exhausted. He was burnt out. When his contract with Capitol Records—”Capitol Punishment” he called it—expired in 1976, it was the first time in 15 years he wasn’t obligated to produce music for a corporation. So his five-year seclusion was a time of lying fallow and recuperating from the intensity of being a Beatle.

AMFM Magazine: Was this isolation a period of creativity for Lennon?

The bulk of John’s creative energies during his five-year period of isolation went into his diaries, which he wrote in every day, sometimes upwards of a thousand words. The diaries struck me as a rough draft of a tell-all memoir that he never had the opportunity to complete, and I discuss them at length in Nowhere Man. Much of the writing had to do with his rivalry with Paul McCartney, but he also wrote a lot about his relationship with Sean and Yoko. In 1977 and ’78, he spent time programming dreams with a technique he called “Dream Power.” He’d then wake up and record those dreams in detail. He also wrote the manuscript for Skywriting by Word of Mouth, which was published posthumously.

As far as music, he wrote a couple of songs that he didn’t think were good enough to release, and he came up with a germ of an idea for a song that eventually became “Watching the Wheels.” But his years of seclusion were not a fertile period of musical creativity. It was in 1980, when he chose to return to the world, that he was able to reconnect with his muse and write the songs that were released on Double Fantasy and posthumously on Milk and Honey.

AMFM Magazine: Why did he get involved with various belief systems such as Buddhism and the occult?

Though he mentioned it in “Serve Yourself” (“You say you’ve found Buddha sittin’ in the sun”), Buddhism was not something that often came up in the period that I’m most familiar with, Lennon’s years of isolation from 1975 to 1980. Christianity, however, did. This is how I describe his Christian period in Nowhere Man:

John, in 1977, out of sheer boredom, had taken to watching preachers on TV. It was something else to do besides sleep and program dreams. Despite his better judgment, he somehow became a big fan of the Reverend Billy Graham. At first he watched only for entertainment. Then, one day, he had an epiphany—he allowed himself to be touched by the love of Jesus Christ, and it drove him to tears of joy and ecstasy. He drew a picture of a crucifix; he was born again, and the experience was such a kick, he had to share it with Yoko.

His born-again period lasted for about two weeks.

As for the occult, this was something that Yoko had gotten John into. She was into all the occult stuff big time: magic, astrology, numerology, tarot. She went to Colombia, in South America, to pay a powerful witch $60,000 to teach her to cast magic spells. They had a full-time tarot card reader whom they called Charlie Swan (his real name was John Green). Yoko would confer with him every day about everything, and John would confer with him frequently, often about investing in gold futures. Swan was, essentially, their business advisor, marriage counselor, and psychiatrist. They didn’t make a move without first having Swan do a tarot reading. When John and Yoko hired people to work in the Dakota, they’d analyze their numbers according to Cheiro’s Book of Numbers; they’d analyze their horoscope; and of course they’d have Swan do a tarot reading.

John and Yoko saw magic, in particular, as an instrument of crisis management, a weapon, and a system to help them make money. Because they both had a powerful imagination, which is the magician’s most important tool, they believed that it was possible to use magic to control their enemies. John, for example, believed that Yoko had brought about McCartney’s arrest in Japan for smuggling marijuana by using a magical spell she’d learned from the Colombian witch.

AMFM Magazine: Did John communicate with Paul McCartney when isolated inside the Dakota?

There was a brief period in 1976, after Sean was born, when Paul would show up unannounced at the Dakota, talk his way past security, and knock on John’s door. Sometimes he’d bring his guitar and sometimes he’d bring his wife, Linda. John would let them in. They’d hang out and watch TV. But John began to resent the unexpected intrusions and told Paul to call before he came. Paul felt rebuffed and he stopped coming by. They didn’t see each other again until sometime in 1977, when John, Yoko, Paul, and Linda met for dinner at Le Cirque, Paul’s favorite French restaurant in New York. John had a miserable time and regretted going—because Paul and Linda went on and on about how their lives were perfect, how they had everything they’d ever wanted, and how they were as happy as they’d ever been. After that, John and Paul had little direct communication—until January 14, 1980. That’s when Paul stopped off in New York on his way to Japan with his band Wings, and called John at the Dakota, offering to come over and turn him on to some excellent marijuana. John declined. Paul told him that in Tokyo he was going to stay in the Okura Hotel’s Presidential Suite. John flipped out. He considered it his and Yoko’s private suite and was repulsed by the idea of Paul and Linda sleeping in their bed. He thought they’d ruin his hotel karma. Yoko then claimed to have used her magic powers to curse Paul and have him busted at the Tokyo airport for smuggling marijuana. John was thrilled when this actually happened and Paul spent ten days in jail. John loved Paul like a brother. He just couldn’t stand being around him.

AMFM Magazine: What was John’s relationship like with Phil Spector, while recording the Rock ‘N’ Roll album?

Lennon recorded Rock ‘N’ Roll in 1973 and 1974. His diaries cover 1975–1980. The only mention of Phil Spector is after John and Yoko finished recording Double Fantasy. Yoko was considering using him to produce their next album. So John obviously had forgiven Spector for the incident that had occurred during the Rock ‘N’ Roll sessions: Spector had pulled out his revolver and, holding it inches from John’s ear, fired a shot into the control room ceiling. John then famously quipped, “Phil, if you’re going to kill me, kill me. But don’t fuck with my ears. I need them.”

AMFM Magazine: Could you tell us about John Lennon’s fight to stay in the United States?

This happened in 1976, in the months after Sean was born, when John was obsessed with his new baby and the idea that he finally had a real family. He’d pretty much stopped writing in his diary—about everything. There wasn’t a word about his father’s death or Mal Evans, the former Beatles road manager, whom L.A. police shot to death in a motel room, or that his contract with Capitol Records had lapsed. And there was almost nothing about the immigration battle.

The threat of deportation had been hanging over Lennon’s head for four years because of a 1968 marijuana conviction in England that the Nixon administration had used as an excuse to brand him an “undesirable alien.” In the spring and early summer, as the immigration hearings approached, Yoko was busy persuading people like Norman Mailer and Cardinal Cushing to testify as character witnesses for John. John, meanwhile, went with Sean to Long Island, where he tried to relax by meditating and sketching sailboats.

John’s application for a visa was approved July 27, 1976. Sean’s birth nine months earlier had apparently clinched the decision. The government, apparently, didn’t want to break up a family. John was amazed that the Irish justice voted against him and the Jewish justice voted for him. He vowed to plant a tree in Israel. That was all he wrote in his journal.

So Johnny got his green card and was a permanent United States resident. And that’s when his years of seclusion officially began.

AMFM Magazine: Did a lone gunman kill John?

I’m aware of the various conspiracy theories floating around, and I said in Nowhere Man that I think most of them—Manchurian Candidates, for example—are based on scenarios so complex, they’d be nearly impossible to carry out. My understanding of the psychology behind conspiracy theories is that certain people cannot accept the fact that horrendous events, like murder, can be totally random and can happen to anybody. So they need to invent stories, impervious to rational evidence, that give them a sense of control and show that it can’t happen to them. So, yes, I think Mark Chapman, a deeply disturbed and probably psychotic individual, was a lone gunman. Chapman believed that by shooting Lennon, whom he considered a hypocrite, Chapman would literally vanish into the pages of The Catcher in the Rye and become the Catcher in the Rye for his generation. An actual trial, rather than just a sentencing hearing—after Chapman changed his plea from not guilty by reason of insanity to guilty—would have been better. The evidence would have been examined and it would have been proven beyond all reasonable doubt that he was the lone gunman (not that the conspiracy theorists would have cared). But the end result would have been the same. He was going to be locked up somewhere for the rest of his life and it wouldn’t make much difference if it were a maximum security psychiatric hospital or a prison, which is where he is and where he belongs.

Robert Rosen is an American writer born in Brooklyn, New York, on July 27, 1952. He is the author of Nowhere Man: The Final Days of John Lennon, a controversial account of the ex-Beatle’s last five years, based on Rosen’s memory of Lennon’s diaries.

Robert Rosen is an American writer born in Brooklyn, New York, on July 27, 1952. He is the author of Nowhere Man: The Final Days of John Lennon, a controversial account of the ex-Beatle’s last five years, based on Rosen’s memory of Lennon’s diaries.

His second book, Beaver Street: A History of Modern Pornography, was published by Headpress in the U.K. in 2011 and in the U.S. in 2012. The Erotic Review said of the book, “Beaver Street captures the aroma of pornography, bottles it, and gives it so much class you could put it up there with Dior or Chanel.”

A memoir, Bobby in Naziland: A Tale of Flatbush, was published by Headpress in 2019. The Jewish Voice said that the book portrays Flatbush “with the characterizations and insight of a good novel…. But it really is the neighborhood that’s the star of the story. You don’t have to be Jewish—or a Brooklynite—to be enchanted by this book.” The book was re-released in 2022 as A Brooklyn Memoir: My Life as a Boy.